Norbert Freedman, Richard Lasky, & Marvin Hurvich [An abbreviated version of this paper was presented on June 9, 2001, at the Annual Meeting of the Rapaport-Klein Study Group]

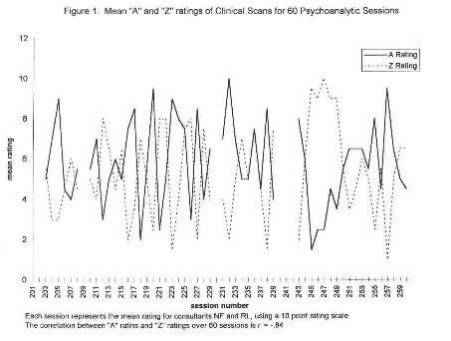

Historical Perspective We are blessed today with a rich repertoire of objective methods evaluating analytic process. Each seeks to capture bits of analytic work: the CCRT (Luborsky's Core Conflictual Relational Themes; Luborsky & Crtis-Christoph, 1990) in the referential cycle (Mergenthaler & Bucci, 1999) not only sub-symbolic processes, but also derivatives of unconscious fantasy; in FRAMES (Dahl, 1988) aspects of the compulsion to repeat; in PERT (Gill & Hoffman, 1982), the perceived relationship to the therapist; the Scale of Structural Change (Wallerstein, 1988a); Jones' Q-Sort approach (Jones & Winholz, 1990); and, the comprehensive process scales by Waldron (1999). Each of these is valuable in its own right. However, in the application to the study of process these methods have relied almost exclusively on transcripts. The issue of what is the proper database for defining psychoanalytic process, debated in the House of Delegates of the EPA during the work of the Committee on Psychoanalytic Specificity. The question was: "What is specific about the nature and consequences of analytic process?" In spite of wide theoretical divergences the group agreed fairly readily on a broad outline. Specificity involves transference, transference-regression, interpretation, the recognition of the symbolic, and the judicious use of countertransference. However, when the question of validation was raised so that these processes may be documented on a consensual basis, strong disagreements emerged. The main argument was "I know my patient's unconscious and my own countertransference, so only I can estimate the crucial events through my own subjectivity." In fact, the work of prominent empirical researchers was cited as setting a dangerous precedent on the grounds that 'process' relied on recorded sessions apart from the perceptions of the engaged analyst. After lengthy debate, a compromise, indeed a reasonable synthesis, was arrived at. What at first seemed to be incompatible views were reshaped into a position statement that included four points: (1) any effort at validation must be rooted in the history of psychoanalytic clinical thought; (2) the evaluation of process should originate in the subjective and intuitive judgment of the engaged and experiencing analyst; (3) evaluation should be corroborated by consultants using the time honored methods of peer review and supervision, and (4) only then would these essentially clinical procedures receive external validity through the study of recorded texts. This ideal prescription was accepted by the house and was communicated as a news release and was sent to all IPA Societies in the three regions. These recommendations were internalized and incorporated into our Institute for Psychoanalytic Training and Research (IPTAR) Research Program: "Can psychoanalytic process be defined empirically?" and the "Method of Sequential Specification" was the result. Before detailing our steps of implementation, some thought must be given to the assumptions and conditions of observations, which guided our endeavor. The analytic process is a promissory note, suggesting the conditions favoring a salutary analytic treatment. It is also a code word defining the identity of training programs or quality of treatment proffered. Its absence is a pejorative, as in "an analytic process has never developed. " It has the potential of being a word of praise or of condemnation. It is an illusive notion difficult to specify. We took up this challenge by asking: "Can it be defined in a manner that is clinically persuasive and empirically valid?" In this fashion we hope to offer a common ground for analytic inquiry (Wallerstein, 1988b). An Approach to a Psychoanalytic Knowledge Base "What kind of analytic research do we want?" queried Andre Greene (1996) in his controversial discussion with Robert Wallerstein (1996). Greene outlined a view of infinite contextualization, with the analyst immersed in varying states of consciousness experiencing intra- and inter-subjective images converging simultaneously. Under such conditions, quantification is well nigh impossible. Wallerstein retorted that even with a full appreciation for the complexities of co conflict and of context, it is nevertheless feasible to fashion a method that approximates the rigors of science. This is the vision, which we pursue. To state the issue in another way: How are we to learn about the psychic events that matter? Are we to rely upon the subjective meaning structure that evolves within the analyst or within the analytic couple? Or, will the tilt be in the direction of external confirmation governed by the canons of systematic inquiry9 This issue dates back to a deep ambivalence in the writings of Freud over five decades (1914) and it has more recently been codified in the opposition between a hermeneutic and a scientific perspective. However, in our 'Method of Sequential Specification' we shall speak not of an opposition, but a continuing dialogue between these two domains of knowing. That inevitably leads to different sources of observation as well. Our inferences about analytic process are rooted in three sources of observations. First, there is the report of the experiencing analyst. Second, engaged in the heart and spirit of the interchange there are the observations of consultants listening both to the analyst report as well as to the recorded session. From this source of observation, there is a very detailed examination of the event structure, moment by moment inside the analytic hour. Finally, there is the recorded session as text available for external often computerized study. We think of these levels of inference as the Rashomon tendency in attempts to understand analytic treatment. This approach to psychoanalytic inquiry is a way of dealing with the apparent dichotomy between a hermeneutic and a scientific perspective. In this apparent dichotomy, between understanding and consensus, between contextualization and validation, we spell out a particular dialogue. It is not a dichotomy, as suggested by Greene (1996), not a midpoint between two extremes (Leutziner-Bohleber, 2000), not a conjunction as suggested by Cortini as well as Silverman (1999). It is an ongoing dialogue, which starts with and is rooted in the immersion of the observers in the situation of clinical immediacy, which, as the mode of observation changes, reaches toward objective confirmation. We hold that through this method we approximate this dialogue. The Method of Sequential Specification: From Immediacy of Clinical Experience to Objective Confirmation Sequential specification appears to be the appropriate term for our project, which aims at capturing the specificity of analytic work. Our procedures start with the basic database: recorded psychoanalysis conducted within the frame of the psychoanalytic method. But then you will note that the inquiry moves systematically from intuitive observations, to confirmation, to specification, and then to external validation. It is a method in which a single session undergoes, evaluation through four successive passes. In outlining our method we are not offering a manual, which yields a ready evaluation of recorded text. Rather we are suggesting a set of procedures, with each guided by certain precepts and challenging questions: how to capture the immediacy of the analyst's experience of the session; how to confirm that initial impact by entering, as it were, the analytic hour; how to specify the event structure through fine-grained scrutiny; and how to select validating criteria that are clinically persuasive and reliable. These four procedures are guided by one common consideration: temporality. Psychoanalytic process always entails events before and after, moment to moment, within a session, across sessions, and across the course of treatment. Analytic process always has a cyclic aspect, and recognizing this lead us to define transformation cycles which function as organizers of the course of treatment. Capturing the immediacy of the session: The working session and the difficult hour "The patient was extremely anxious at first, she saw her dilemma and I sensed what she wanted from me, I felt I knew herů" "The session didn't seem. to go anywhere; the material was chaotic, I felt attacked and irrelevant." These are the kinds of thoughts and feedings that may permeate an analyst's consciousness just after the patient has left the room. We share the sentiments of those critics who suggest that, with such utterances, certain issues surface that are just being digested, not quite metabolized. We obtain a sampling of these thoughts by asking the analyst to record a "clinical scan" Immediately after the patient leaves the room. These consolidated reflections of experiences just encountered can then become the subject of translation and interpretation. We consider not only the content but also the tone and any other emotional factors that may be included in these utterances. This is what we wish to capture. It is our first entry into the evaluation of analytic process and the first thrust toward specificity. At points of polarization these immediate experiences give the feel of an "easy" hour or a "difficult" one. To be sure it is only an interpretation, a translation by the researchers. But it occurs with the quality of a convincing phenomenon. We do not know at this time what the properties of the hour are; this will be discovered shortly. However, even in this first approximation we surmise that these immediate reflections will point to organizers of an entire session. They form a Gestalt. The listening clinician perceives this Gestalt as either having the feel of a working session or a regressive one. And, from a more systematic vantage point; we may speak of an integrative hour and one marked by non-integration. The prevalence of these organizers can define entire sessions. The first we have termed an W type session; the second a 'Z' type session. We deliberately chose the abstract designation so as not to prejudice the specific content that may be implicated. Once we introduce such designators - designators that identify crucial moments in analytic treatment - we can also assume that they may undergo sequential alternation from session to session. That introduces the temporal dimension in the evaluation of process. But before elaborating this further, we must describe the task of substantiating the appraisal of the initial scan. Inside the analytic hour: Confirmation and choosing a descriptive language Was it really an 'A' hour, or a 'Z', as described by the analyst? This is our query as we appraise the impressions gathered by the initial clinical scan. At this point, two consultants listen to a recording of the entire session. As they immerse themselves in the matrix of feelings, actions and interactions, they seek to determine whether this was, from their perspective, an 'A' session or a 'Z'. This is the second step in the evaluative process and with it comes the next move toward specificity. This evaluation of an entire session cannot be undertaken without the use of a descriptive language which is clinically persuasive but which also can find acceptance among a broad range of psychoanalytic thinkers and practitioners. We feel that a recorded and transcribed session, conducted on the spirit of the analytic method, provides a wide database for evaluation of many often diverse psychoanalytic views. Our methodology was guided by Waelder's (1962) levels formulation. We utilized the three lower levels: clinical observation, clinical interpretation, and clinical generalization. These three levels are the ones Waelder specified as the most important for developing hypotheses from a psychoanalytic perspective. Hence we ask the consultants to describe the session along the lines of assessing levels and forms of anxiety, defenses, of ego organization, of mayor object relations conflicts, and of indicators of transference and counter-transference themes. While any of a number of recorded sessions could be chosen for this clinical appraisal the interest here is in targeting criterion sessions for study. Specifically, sessions characterized as high 'A' and high 'Z' are selected for this phase of confirmation. This step places us in a position to strengthen our confidence in the clinical significance of 'A' or 'Z' hours. It shows that it is possible to identify criterion sessions that reflect an accord between the engaged analyst and the independent consultants. In the event of a confirmatory judgment, we can find support for the notion that the judgment of the initial scan indeed portrays a process of positive seeming analytic work or negative seeming analytic impasse. Moreover, such observations also suggest that distinct kinds of mental processes are at work in the patient, in the analyst, and in the dyad. Neither an 'A' session, a integrative one, nor a 'Z' session, a regressive hour, can account for analytic process alone; it is in the alternation of the two that analytic work takes place. Such a formulation inheres in the view that controlled regression is a crucial condition for the working ego to assimilate previously intolerable tension states. Yet to support such a view calls for greater scrutiny of the event structure - the properties - that comprises the criterion sessions. Specifying changes in mental functioning All analytic process entails change and changeability, as Abend (1990) has noted. But that is a very broad statement. There can be macro-changes extended over a developmental phase (Kris, 1951; Greenacre, 1968), and such change in process can permeate across a range of sessions. There can also be micro-changes, exemplified by Gray's (1982) fine-grained examination of the analytic process. We Wish to specify the events and event structure as they arise from moment to moment, and thus contextualize the seemingly 'difficult' or the seemingly 'working' session. In this focus on the change of functions, we speak not merely of the usual components of process, viz. free association or resistance, but particular shifts in these functions in the course of an hour. Process implies the encounter with new mental experiences. To discover and comprehend such novel moments, as they unfold, we listen to the recorded session once more accompanied by a careful reading of the transcript as the third pass of our method. In this effort of specification we seek to internalize the listening stance, be it that of analyst or supervisor. We listen to the hour and are on the look-out for shifts or changes in how mental functioning is being employed; we give a change a notation and call the materials on either side of the mark a 'unit.' For example, if the patient tells a dream and then adds, "It reminds me of my grandmother making macaroni and cheese," we give this shift a mark. Or, I am thinking of fixing my living room and then I get a flash about the way you arrange your chairs," we give this flash a mark. Or, "He looked at me and then seemed chagrined the way you do," and we mark the reference to the analyst. These markers are the signifiers of our recognition, our discovery of an alteration in how mental functioning is being employed by the patient. They are recorded by two analyst listeners who lay out the entire session portraying these unfolding events. At times there may not be any markers for a few minutes; at other times there are several taking place almost at once. In order for marks to be inserted, they must be so convincing that they yield to the consensus of both observers. The full process of specification actually entails two readings of the session. The first involves the laying out of the psychic events - the units - and the second involves defining the properties that depict each unit. As can be expected, these properties follow closely the previously mentioned choice of metapsychological "mainstream" description Hence we note changes in reflective functions, concreteness or de-symbolization; shifts in the level of anxiety, be it of loss or annihilation; shifts in other aspects of tension regulation; sudden shifts in affect; alteration in the representation of objects, in the past or the here and now; and of course shifts in the transference, in or out of the session. Attention is also given to shifts in the level of consciousness, from surface to depth or the reverse. It is evident that our account so far has focused on the mental events in the patient. Of equal importance to us are shifts in the analyst, e.g., the timing and appropriateness of interventions. We also consider long pauses, interruptions, or concurrent speech, which reflect upon the state of the dyad. The synchrony or asynchrony of this interaction gives an index of the extent to which the participants are in synchrony with each other. Such observations speak of course to the role of intersubjectivity in the transference/counter-transference matrix. The result of this effort is the landscape of mental functioning during a given hour. The assembly of units gives a picture of altered functions as they proceed throughout the session. As will be shown in our observations below, this panorama is quite different for a working compared with a difficult session. It will be distinct in its surface saliency, its gradient of changes in the course of the hour, and its overall contextualization. It will point to the progression of psychic events, and the manner conflicts are resolved. It is of central importance that the overall event structure, the configuration, should be persuasive to any good-enough clinical observer. Whereas the choice of individual units, blow by blow, are undoubtedly a source of dispute, the overall pattern, taking the session as a whole will yield congruence (hence, for pattern recognition, we eschew the use of a scoring manual). This will be documented. Such concordance would reflect the understanding of psychic events gathered in their context. But whether or not such an effort at systematic clinical-dynamic description is amenable to objective appraisal, becomes the goal of the next task. External validation The transcripts of the recorded session are now subjected to independent, this time manualized procedures of evaluation. We ask whether an 'A' or a 'Z' session so far identified by the indicators of change in mental functions will also reveal divergent patterns of response on measures far removed from the subjective modes of listening by the consultants. With the application of 'external' validating instruments to our criterion sessions we are entering the dialogue between a hermeneutic understanding of clinical process and scientific, hypothesis-driven validity. To be sure, the simple correlation between the context of units and any of the empirical measures with which we started our reflections will provide reliability and clinical validity to our profile of analytic process. Yet, there is another way to think about the enterprise of external validation. The profile guided by the units was rooted not just on a specific psychoanalytic theoretical perspective but also on a mode of convergent listening. This includes the recognition of multiple, concurrent properties apprehended within a single unit, all in dynamic relation to each other. For example, reflective functioning co-occurs with specific forms of tension regulation, within a context of object relatedness. This intertwined, teleologically-driven set of psychic events is precisely the way a clinician listens, and it is one way of understanding the dynamics of clinically relevant meaning. The introduction of validating measures, each based on a single explanatory dimension, lends, perhaps, a further specificity to our knowledge of what regulates process. It can lead to new discoveries. Here we enter the sphere not just of clinical validation, but also of construct validation. The application of measures of Referential Activity (RA) is a strategic starting point for the endeavor of external validation. The concept and its measurement has a substantial empirical foundation (Bucci, 1997). RA reflects a quality of spoken language that is evocative, elaborate, and specific, and points to qualities of self-reflective thought. It describes levels of spoken thought in terms of sub-symbolic as well as symbolizing processes and it offers a measure of change as well as a measure of cycles within sessions. There also is a computerized version of RA, the CRA, with good reliability (Mergenthaler & Bucci, 1999), and it is this version, which was applied to our criterion sessions. The CRA evaluates not just RA, but also emotion tone and abstraction, and the interplay between these and the analyst's speech. The shape of an apparently difficult or working hour, first gleaned from. the analyst's consolidation of experiences right after the session, confirmed by the reading of the transcripts, specified by the scrutiny of fine grained listening, now can receive further articulation through computerized language programs. And, the discrimination is not just one between sessions, but also a gradient of shifts that takes place within the hour. That introduces a final, important theme of our method. The temporal dimension in analytic process transformation cycles The issue of time has entered into every consideration in the study of process. This is the "when" in the examination of critical events. We can note it in the distribution of 'A' and 'Z' sessions, their peaks and troughs in the course of a single year of treatment; we can note it in the selection of criterion sessions only about five or six days apart. Then, when we went inside the analytic hour (and with it the scrutiny of moments of change or even in the analysis of language use) a gradient of change in the course of a single hour became a critical differential. Hence time becomes a factor, from moment to moment, from session to session between weeks, months, and even years. The issue of time has been much neglected in the empirical study of process. For example in the otherwise excellent review on the subject by Vaughan & Roose (1995) who introduced the Columbia Analytic Process Scale (CAPS), the evaluation of process, examining whether it could be discerned by an observing analyst, was based on a single hour. They failed to obtain acceptable levels of validity. It is our view that the presence or absence of a mutative process cannot be determined unless the naturally occurring alternations, within sessions, or between are given serious consideration. Indeed it is the cyclic alternation of events, their peaks, plateaus, decline, and resurgence that are often telling signposts. It is a notion that has led us to regard transformation cycles as organizers of the analytic treatment process. This notion of the transformation cycle as an inherent aspect of analytic process has a spotty history in the annals of analysis. It begins with Abraham's (1913) classic paper on manic-depressive psychosis, where he spoke of the depressive, the manic, and the in-between periods. More recently Betty Joseph (1997) has spoken of micro cycles that point to shifts in the surfacing of projective identification, and O'Shaughnasey (1997) has described macro cycles in defensive re-organization. The most recent relevant work is by Mergenthaler & Bucci (1999) who discuss referential cycles; they have noted cyclic development within a given session as well as across sessions over years. These authors suggest that the organization of mental activity within a session is isomorphic with alternations taking place in the course of an entire analysis. The question naturally anises, what is the psychic quality that undergoes cyclic alternation? In earlier work we have centered attention on shifts in symbolization and de-symbolization, modes of thought not far removed from attributes of analytic work or regressive impasse (Freedman, Berzofsky, & DiMichele, 2000). Transformation cycles are ubiquitous phenomena arising in all the psychotherapies. They differ in duration, frequency, and intensity. They also vary with diagnostic groups, type of treatment proffered as well as patient-therapist match. In the present research, of course the concern is with the cyclic alternation in qualities of A-ness or Z-ness. We are suggesting that it is the analytic situation, the frame, that will accentuate the recurrent oscillations of analytic work and/or impasse. Once it becomes possible to pin-point phases in the course of analytic treatment - first, phases in which there are signs of integrative analytic work (i.e., 'A' sessions), and second, phases which are difficult and regressive (i.e., 'Z' sessions) - we have at our disposal at least one cycle that depicts the range of analytic process. Such cycles can be replicated over succeeding hours during one year, or, for that matter throughout the entire analysis. With such a graphic representation of the peaks and troughs of analytic work, we obtain a methodology which can address some clinical issues of far-reaching implications. Thus, by identifying the psychic events occurring at the peak of a cycle, the 'A' session, we can formulate hypotheses regarding the forces at work just before the slope of decline, which are the precursors of regression. Conversely, when the focus is upon the trough of the cycle, the 'Z' session, just prior to ascendance toward new integrative work, we can make inferences about the play of reparative forces. Here the model of sequential specification can shed fight on the induction of regression, forces pulling toward disintegration or about the recovery from regression, and with it the dynamics favoring repair. These are the implications of the role of cycles in the course of analytic work. The play of peaks and troughs give vivid demonstration of the contradictory and apparently incompatible states, which are the very essence of the process we seek to illuminate. For process is not simply the saliency of one attribute or another, be it work or regressive disorganization. Rather, it is in the alternation of the two, in sequence, that analytic work can proceed. To conclude: the basic data of this study will rely on a single transformation cycle, the study of a 'Z' session followed by an' A' session about six sessions later. For each session we shall travel the road of sequential specification; from the initial scan to its confirmation, specification, and external validation. Then, a second cycle for the same year will also be selected in an effort toward replication of the analytic process during that year. It offers a definition of an analytic process during one year of analysis. We have at our disposal data for successive years of this analysis so the identical steps can be repeated. It becomes evident that the study of successive transformation cycles offers a methodology for the definition not only of process, but of outcome as well. The Method Implemented The psychoanalytic method offers a frame for observation, for it delimits and specifies that which we are about to discover. Within this frame we find the well-known tools of analytic technique: reliance on free association, interpretation, and the recognition of resistance and it's working through. They are the major components of analytic work as spelled out by Freud, which have persisted today, albeit in many quarters, with very divergent emphases. Vaughan et al. (1997) have given an excellent summary of this extensive literature, and have shown that these pillars of analytic work are present in only about fifty percent of patients participating in an analysis. However, when they do occur, they are powerfully predictive of subsequent positive treatment outcome. This fact makes it imperative that we scrutinize those aspects of the method that shape the long-term course of treatment. It is precisely this scrutiny, this thrust toward specificity that is the goal of the present inquiry. The Patient, the Analyst, the Frame, and the Scan "Patty" and a sketch of her clinical issues Patty is a woman in her thirties, mother of a three year-old boy, and a girl, now 2. She fives in a suburban Midwestern community with her husband, a professional man, and secure income. She started a twice a week psychotherapy about six years ago and in her second year converted to a four times a week psychoanalysis. The tone of the treatment shifted dramatically over the first three years of the analysis. The initial transference was one of non-engagement and affective withdrawal; some time later this developed into a sadomasochistic transference, and then further into an explicitly erotic transference. These transference tensions have been expressed by the enactment of a scheduling ritual at the being of virtually every session. The transference intensity may well have been one of over-engagement - a defense from an essentially schizoid position at first, but as the treatment progressed we witnessed acute neurotic conflicts. It is at this stage, in which neurotic conflict is paramount, that we entered the study of the treatment process. The Analyst and the Treatment Frame The analyst is a woman in middle age, a graduate of a psychoanalytic Institute with 12 years of analytic experience. With great consistency she sustained a treatment frame guided by 'classical' analytic method. The patient is seen on the couch four times per week, and the major explicit tool of intervention is verbal interpretation. This does not imply, of course, that the analyst is not constantly aware of the nonverbal as well as verbal aspects of transference and countertransference. Even though the patient's initial clinical picture, that of a kind of schizoid defense, showed the presence of very primitive ego organization, the basic structure of the analytic process was possible throughout the treatment. Within this frame, the analyst introduced tape recording at the end of the third year of analysis. She explained the research objective to the patient and obtained her written consent. Thereafter, taping was rarely an issue. The analyst set up the recording equipment prior to the onset of a session, so it was no longer a manifest event m' the conduct of the session. There is every indication that even when it became a vehicle for other issues, the audio recording did not prove an obstacle to the development of all the process characteristics about to be described. The Clinical Scan. Immediately, at the end of the session, with the tape recorder still on, the analyst dictates her impressions (for 3-5 minutes) of the session just completed. The scan typically covers mayor aspects of object relations, self feelings, anxiety and tension states, transference and countertransference themes, and a free ranging estimate as to how the session had gone. For the analyst, the scan is a time for reflection, sometimes even emotional discharge, but it is also a special kind of reflection; that is, a summing up while the dynamics (both the patient's and the analyst's) are still active and finger on. As the analyst has noted, "the session is very much alive in me when I record the scan." This method of the clinical scan has been in use for some years in the evaluation of psychotherapy process and was developed at the Downstate Medical Center by Berzofsky, Wilke & Freedman (2000). A tape splicing procedure makes this scan a powerful research instrument. It is possible to transfer about twenty scans (or five weeks of analysis) onto a single tape,. It is actually pleasurable for colleagues to listen to the development of a year of analysis, session by session, in one sitting. To date, we have about 260 sessions from the third, fourth, and fifth year of the analysis. Sixty sessions from the fourth year form the basis of this report. On these data, the method of sequential specification is implemented. Specifically, we launch four particular passes of data analysts: 1) the clinical scan and the initial estimate of process; 2) confirmation of the initial estimate and the selection of criterion sessions, 3) specifications of mental functioning in criterion sessions, and 4) external validation. Pass One: The Initial Estimate of Process The scan is our entry into the evaluation of process, as it originates in the analyst's immediate experience of the session just completed. The clinical scan provides not only an initial approximation of process properties, but also the distribution of process characteristics over the range of sixty sessions of analytic work. This first entry into the evaluation process was carried out by two consultants (RL and NF). As we already indicated, we listened to these scans with an ear toward discovering in those scans qualities of 'A-ishness' and 'Z-ishness', as we chose to call it, and gave each session an estimate an 'A-ish' as well as a 'Z-ish' quality, having the feel of an integrated session or a difficult-regressive session, respectively. The consultants, working independently, provided two scores for each session: a score for 'A' and a score for 'Z'. Across 60 sessions, the correlations between consultants for A-Ish qualities was r = .59 and for Z-ish qualities it was r = .72. We calculated an average 'A' rating across consultants for each session and an average 'Z' rating across consultants for each session, to determine the correlation between the 'A' and 'Z' qualifies themselves. The resulting correlation was r = .84. Mean 'A' and 'Z' scores (i.e., across consultants) were used in our graphic representations. The distribution of mean 'A' and 'Z' ratings per session for each of the sixty sessions are shown in Figure 1. As expected and noted, there is an inverse relationship between 'A' and 'Z' sessions. Note that the graph also indicates that both of these properties of process are present within each session. lie graph further reveals that certain sessions peak at 'A' with minimal 'Z' quality and other peak at 'Z' with minimal 'A' quality. Nine predominantly 'A' and six predominantly 'Z' sessions were our potential criterion sessions. These 15 sessions become the target for farther study.

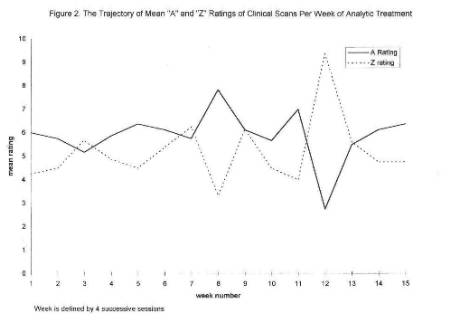

We should also note the cyclic alternation of 'A' and 'Z' predominance over the course of the analysis. Since this is a four-times a week analysis, we found it instructive to consider average 'A' and 'Z' rating for blocks of four sessions each. The resultant distribution is shown in Figure 2. It can be noted there appear regularly occurring waves of 'A' and 'Z' pre-dominance over the 60 sessions.

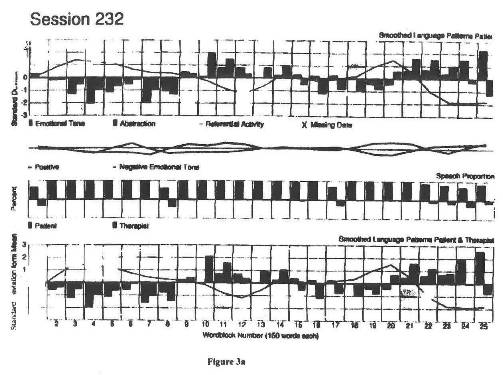

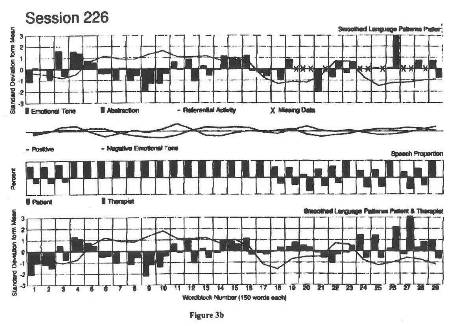

Pass Two: Inside The Analytic Hour: Confirming The Initial Estimate Next we wanted to ascertain whether the judgment of A-ish or Z-ish qualities gleaned from the analyst's scan, immediately following each session, is really present when we consider the recorded session as a whole. The goal is to confirm or disconfirm the process properties and with it define Criterion sessions. The two consultants listened to an entire analytic hour, much like a supervisor would, looking for those features which were guided by our orientation to be sketched out below. As we listened we were compelled by the distinct contours of the sessions. An 'A' quality was that session which gave evidence of reflectiveness about self and others, affect and tension tolerance, engagement with objects past and present, imaginary or "real," and a resiliency towards the transference as well as the countertransference in the analyst, eschewing enactment or dissociation. A 'Z' quality session was one in which many of these 'A' qualities were absent. However, there were definite and unique indications of 'Z-ishness' as well. Reflective functioning appeared concretized, desymbolized, or regressive; tension regulation leading to enactments was marked; object representations were constricted; and transference implications disavowed. In the analyst, there were more prevalent instances of countertransference enactments. We also noted difficulty in listening and displaced interpretations in the analyst. The consultants listened together and arrived at a consensus. The question of whether it was an 'A' or a 'Z' session was not generally difficult to ascertain. Sometimes, there was a disagreement between the initial estimate from. the Clinical Scan and the confirmatory judgment, based on listening to the entire session. In those instances we would infer that the discrepancy might be a sign of countertransference (these cases form an interesting sub-sample for the further study of countertransference phenomena). Our listening resulted in choosing sessions suggesting cycles: Session no. 226 was a 'Z' session, which was followed by an 'A' session six sessions later, no. 232. Then we chose a 'Z' session, no. 245, followed by an 'A' session, no. 257. These 4 sessions offer an opportunity for replication of what we have termed a transformation cycle. Pass Three: Specification of Changes in Mental Functioning The consultants once again listened to and read this session to monitor the changes in mental functioning, unit by unit, and sketched out its properties. But now in this fine-grained analysis, the units were evaluated not just by the language of clinical description but also by the language of clinical interpretation. Each unit was considered in terms of well-trod. spheres of mental functioning - tension tolerance, affect naming, reflective functioning, object representations, and the transference. There were units of patient speech, analyst speech, and qualifies of non-fluencies - working pauses and disruptive pauses. More important than the content of any individual unit was the evolution over the course of the hour, the way the hour seemed to move. It is this mobility that can lend a quality of direction to an 'A' session; and conversely, a sense of relative stasis to a 'Z' session. These categories are not mutually exclusive of each other, for they interpenetrate one another and it is this interweaving of concurrent events over time that becomes the basis for inferring dynamic meaning. It is analogous to a Rorschach protocol wherein each determinant alters the meaning of the whole. Summary profiles of the content material from. two criterion sessions, an 'A' and a 'Z' session follow. SESSION 232: A 'A' SESSION Patient and analyst began the hour with a ritual scheduling enactment. It ended with the comment: "I didn't feel like coming today." The patient noted that she felt in some ways in better emotional control this week then she usually does. She illustrated this with the description of a typical interaction with her mother in the past where what would normally get under her skin now did not. This led her to a memory of a similar experience she had with her grandmother in the distant past that had greatly upset her at that time. This led her to a number of very recent incidents of a similar type she had with her mother, in which she resisted getting upset. She then became confused and was not sure whether or not she had actually said something she thought she said in that incident. Ile analyst seemed to be made uncomfortable by this and made a deflecting intervention about the concrete features of the incident. The patient complied by recounting the situational aspects of the incident and then went on to talk about the relief she feels in not being overly antagonistic toward her mother. She then spoke of her relationship to her father being better and illustrated this with a story of how he watched her breast-feeding her infant - how it did not seem uncomfortable and how he was a watchfully hovering helper to her. She explicitly commented that it was not sexual, which led her to speak about positive feelings toward the analyst and why she was looking forward to that day's session [yes, this is a reversal]. She spoke about the conflict she had about a house she was thinking of buying particularly as it related to her childhood. As she described her mixed feelings, she speculated that she had made herself less emotional today as a defense that would keep her from opening up to the analyst, whom she painfully looses each time a session comes to an end. She then thought of ways she tries to contain her feelings of sadness and loss. This led her to remember a conflict-laden dream that started with sexuality and ended in nightmarish terror. The dream concluded with her screaming "Help me, help me!" and it occurred to her that this was what she is feeling in waking life in relation to the analyst. She then felt abandoned by the analyst and defended against her distraught longing for the analyst by getting angry at her and claiming she does not care if the analyst does not reciprocate her wish for love. The analyst interpreted this, and the patient began a reflective period about her dependency needs in regard to the analyst and how she tries to manage them - sometimes by anger, sometimes by depression and eating, and sometimes by denial. The analyst commented on how difficult it was to be frustrated in this way, which then freed the patient to speak of how angry she was that the analyst will not and cannot reciprocate her love in kind. She described how hurt she was in very vivid language and ended the hour with the comment: I am angry because I am hurt, and I am very confused. I don't want to torture you, but on the other hand I don't want to let you off the hook either... until I understand." This is the sketch of the story told. In most general terms, it points to an upwardly sloping trajectory in the direction of greater cohesion and integration. But it should be noted that each change of mental functioning may have its own path. Moreover, many of the functions (e.g., ego operations, object relations) may co-occur in the same unit, and therefore the simultaneity of mental acts itself is a sign of an 'A' session. A researcher looking for a monolithic line of change will be frustrated. We shall begin the account of the trajectory by focusing on Patty's mode of tension regulation and her ability to name affects. Throughout the session we can note a widening river of affect experience: affect naming, startle reactions, nightmarish fright, verbalized anxiety, momentary affect explosion, expression of masochistic surrender and sadistic wishes, more modulated forms of emotional tone, and then the deployment of difficult feelings in direct communication. In the opening ritual about scheduling we could note blocking and only hinting at negative affect. But we see that she concluded with the direct confrontation: "I don't want to torture you..." Here is the frame of the hour. As the anger builds to a rage, she seeks to minimize its impact, and once more a final affect storm is directed outward. There is a concurrent wide range of reflective functioning. There are transitory troughs pointing to concreteness and de-symbolization followed by reflections about self, about others, and about the here-and-now transference. However, in the middle of the hour, there is evidence both of reflection and regression at the same time (indeed there are two cycles). It is not as if everything is all linear, going only upwards, in a multidimensional universe such as this. This is followed by an upsurge, as reflection becomes more integrated as the patient pulls together surface and more complex material. At the end of the session there is an epiphany, an integrative recognition, which then is followed by a retreat. That is how the hour comes to a close. Variations both in tension regulation and reflective functioning are invoked in an evolving pattern of self- and object representations. Once more there is a widening in the range of images of others; first representations of the self in the immediate surround, images of mother, memories of grandmother, events about husband's actions, references to her son, her adopted daughter and then to the analyst. Note that initially these representations are stated as events, then as memories of the past, then images in fantasy, then in a dream, then once more in the here and now, and finally, directly in the transference explicitly. These are the markers of Kris' (1951) "good hour." What is played out is a shift from interaction to the finding of an inner object, and this includes the contemplation of sadomasochistic wishes toward the analyst. Transference and countertransference experiences move along a similar trajectory. The material shifts from an implicit reference to the analyst in the beginning to forms of masochistic surrender, to explicit sadistic wishes, and then toward the transference resolution. It is a development matched by the analyst's actions. The interventions were well timed and pointed to considerable collaboration. Utterances, reflections, and interpretations seemed synchronized both in affect tone and content. In spite of an initial enactment and a brief moment of defensiveness, the analyst was able to stand by and allow free-associative material to develop. The patient expressed many negative feelings such as "You are trying to ward me off," but the analyst listens without interrupting and was able to move the dialogue forward. Interpretations were phrased to allow the patient to run with the ball. There was one instance of blatant countertransference enactment, noted above, as she became quite defensive. But at the end, she recovers and helps the patient to talk about her sadistic wishes. Added to these qualitative observations, of units we can also find certain objective indicators of an 'A' session. To begin with, in session 232 there were 54 units of patient speech, compared to 32 in session 226, the 'Z' session to be described. There was a distinct pattern of verbal non-fluencies. There were prolonged pauses but they were working silences; the speech at the end of each pause was an elaboration or continuation of earlier material. The analyst was mostly in sync with the patient's rhythmic flow of speech, and appropriate in content. The analyst appeared to be engaged in the patient's subjectivity with minimal disruptive countertransference. Contextualization of session 232: As one reviews the slope of the units one is impressed with the close interplay between psychic force, meaning reflected upon, and access to inner objects, all enlisted in the resolution of the transference conflicts. The force is noted in the shift from startled and blocked affect to the direct ownership of feelings. Reflective functions, ranged from de-symbolization and event reporting to apprehension of multiple meanings. 7be object representations unifying memories; of the past with current relations then came to life in a direct encounter with the analyst. It was a cumulative pattern pointing to greater integration of psychic functions. Session 232 has all the attributes, of an integrative coherent session. What is of great interest is the evolution of the transference, its range, and its oscillation. The absence of explicit core conflict is to be noted in the beginning of the hour, yet the patient used the analyst to further her reflections. She confronted the idea of dealing with a disappointing other, but it did not lead only to negative affect, expressed first in memory, then in dreams, then in fantasy, and finally in here and now interaction. The patient even engages both psychotic-like material as well as its reflective resolution, but the reflective quality is not lost. And from the vantage-point of countertransference, the analyst's tolerance for the negative transference is striking. This illustrates how an 'A' session, with all its integrative features, may also be suffused with negative transference; 'A' does not necessarily mean making nice. SESSION 226: A 'Z' SESSION A running summary of the session. The patient began by commenting on some features of the office she liked and then brought up a scheduling issue with the analyst. They then both engaged in a prolonged version of their ritual scheduling enactment. At the end of this very lengthy scheduling session, one of them (it is not clear from the tape which one) left the room for a moment and gets something related to the schedule. Then the patient talked about how painfully depressed she is - how cranky it makes her and how it makes her snap at everyone; she would just like to go to bed. She next remembered an incident that frustrated, angered, and depressed her. She proceeded to a give an extremely lengthy event report filled with highly detailed description of places and circumstances that bothered her, about how inappropriate people and circumstances were, and how she thought that people in circumstances should have been in reality. In this event report she also recounted in extreme detail an especially frustrating experience she had with her children. Finally, near the end of the event report, she described how depressed her anger at them made her. She then spoke about how guilty she feels about favoring one child over the other. This led to considerable anger at herself, with imagery about stabbing herself and putting guns to her head. When her husband tried to help, asking what she wants, she answered, "What I want is a gun to shoot myself'. She indicated that she was not really actively suicidal, but that she was in an absolute rage with herself. She talked about how very painful it is to have these feelings, "As if I am a screeching violin and could start screeching myself." She then focused her anger on the therapist, and indicated that she doesn't care if her need to be connected and loved is not reciprocated by the analyst. The analyst showed a strong counter-transference, making a series of very lengthy interventions, designed to deflect both the patient's affect and the patient's attack. As the patient's anger was deflected, the analyst was able to recast the intervention in a more constructive way and this leads the patient to reflect upon her experiences a little. The analyst then made a more empathic supportive intervention, which then led the patient to speak more about her wishes toward and disappointments from the analyst. The recognition of her frustrated unhappiness led the patient once again to a rageful accusation against the analyst for her heartlessness for not loving the patient back. The analyst once again made a supportive empathic intervention, but the patient rejected it out of hand and angrily condemned the analyst for trying to seduce her into caring and loving her again. The session ended with the patient alternating between raging at the analyst and fearfully defending against the dangerous wish to melt back into love with the analyst. End of session. A series, of recurrent dissonances in commination seemed to mark Session 226. It was a frustrating dialogue, probably initiated by the patient's state that she carried within herself as she entered the consulting room. The units we had identified with an 'A' session were absent, but now there were signs quite specific to this 'Z' session. Persistent disregulation of apparently unmanageable psychic tension pervaded the hour. It was evident in spoken language, in non-fluencies, and in interruptions. lie hour is punctuated with units pointing to a stormy yet disruptive range of affects, sometimes externalized,- the patient is bothered, angry, ready to scream or screech. Rageful accusations shade over into thoughts and wishes to put a gun to her head. Such utterances are followed by various non-verbal signs of explicit tension, such as sighing and disruptive pauses. There are efforts toward connecting to the analyst, some momentary expressions of pleasure, only to be set aside by massive frustration. The more emotions are felt, the further she slips into a regressed mode of thought. Restriction, even impasse of reflective functioning, was pervasive; this was a distinguishing feature of the session. The initial hackneyed, scheduling ritual, accentuated by concretized enactment, then followed blocking, and then the very long series of detailed event reports all suggested an impasse in Patty's deployment of thought. Affects were named but not elaborated upon; they were blurted out without achieving synthesis. The repetitiveness of thoughts, and the intensity with which they were proffered, suggest de-symbolization as well as concreteness and with it defensive disavowal. Intolerable affects within herself were warded off. Externalization. was a dominant theme either blaming unspecified circumstances or the analyst. Toward the end, there was one further stab of aggressivity, blaming not just the analyst, but the entire therapeutic enterprise as she made herself fee]. worse. Externalization no longer protected her from the consequences of her anger. A sense of directionality was absent. In this session, under conditions of extreme tension there was a preoccupation with self, the world of others had minimal significance, except to the extent that speaking about them articulated her sense of misery. Clearly, the range of object representation was restricted. The units that we had met in the 'A' session - memories of the past, episodes outside the hour, images of dreams, fantasy, and then reciprocal engagement with the analyst - were decidedly absent. Toward the end of the session there is an effort to differentiate herself, yet to no avail. The sense of barrenness was summed up in the phrase, "I do not feel you are there." The hour was marked by a manifest, pervasive, negative transference. There was no effort toward genetic understanding, there were multiple instances of negative affect naming directed toward the analyst, with explicit aggressive engagement. The negative affect was not so marked during the first third of the session. where we noted an avoidance of contact via event reporting. But then. the explicit negative component persists and accelerates as the hour progresses. Following this, violent feelings spill. over from a sense of general frustration to attacks on the analyst, and then to the negation of the entire treatment effort. In this attack the transference assumes an hallucinatory, almost psychotic quality in which all the "as if"-ness of an ordinary transference is lost. The negative transference was matched by a disruptive countertransference. The analyst's interventions were either at a standstill or excessive. During the first half of the session, the analyst did not utter a sound (probably defensively so, albeit that is an interpretation), and then made too many interventions, often inappropriately timed. These interventions took place mostly in the second half of the hour, as the analyst was bombarded by cumulative attacks. As the patient became more insistent, the analyst became more defensive. The analyst tended to interrupt the patient, seemingly to prevent the further articulation of negative feelings. Then the analyst went back to the quality of discourse which we saw in the initial phases of scheduling - "when did it happen," "who was there," "where was it," etc. Toward the end of the hour the analyst concludes with a long formulation in an intellectualizing mode. The hour ends with the analyst, less in countertransference, trying to hear the patient, but the patient, in a deeply regressed transference, does not hear the analyst. The atmosphere of the session was punctuated by certain salient quantitative observations. This 'Z' session had only 34 units, compared to 56 for the 'A' session. It suggests a greater degree of redundancy of thought. There were long silences, but these were fragmented silences and not working ones. The pauses were ended either by the analyst's speech and/or by material that appeared irrelevant to the stream of associations. There was good bit of simultaneous speech showing that the two participants were not in tandem. Contexualization of Session 226: Additively and in their pronounced stasis, the markers clearly pointed to a 'Z' session. We note this in the impasse in tension regulation, in the restriction of reflective functioning, with de-symbolization and concreteness, and in a representation of others, which was profoundly hostile. It was a mode of representation in which the patient found herself entrapped in a therapeutic relationship, experienced as counter-therapeutic, dominated by a pervasive negative transference and by a complimentary disruptive countertransference. It was a countertransference in the true sense of the word, for it countered the patient's negative transference. These were the salient features of the hour. It was a "jagged" interchange without resolution. Comparison between Sessions 226 and 232: Clearly, the two sessions are distinct quantitatively and qualitatively along the properties we have outlined. But what is noteworthy here is a progression of mental functioning within each session; a movement toward or against integration. In session 232, we noted the movement toward more elaborate forms of reflective thought, in more modulated experiences of affect, in the more imbedded experiences of self in objects and objects within self, all leading to a special form of the transference-countertransference matrix. This move toward integration was absent in session 226. However, we must remind ourselves that this 'Z' session preceded the 'A' session by only 6 analytic hours. It would seem that the lack of integration in the 'Z' session is an important precursor to the attainment of integration in the 'A' session. It is this contrasting pattern of non-integration and integration, which are the hallmarks of a transformation cycle and, indeed, it may well be an important organizer of analytic process. We have really now moved from the intuitive description of events into a statement of 'A' and 'Z' in the language of clinical description; but now we are interpreting a Gestalt in the language of clinical interpretation. The constituents of the Gestalt are clinically well recognized (tension tolerance, reflective functions, access to object representations, etc.). But what makes these components into a Gestalt is the dynamic inter-relationship of their continuous interweaving, recognized by any "good enough" clinical analyst. The Problem of Congruence. Will experienced psychoanalysts listening to or reading 'A' or 'Z' sessions comparable to those we have just considered arrive at comparable judgments? This is precisely the task we've begun to explore in our study on clinical congruence. We use the word "congruence," rather than "reliability," as a means of determining joint pattern recognition in keeping with the essential qualitative, clinically- based nature of the judgment. On reading a text, there may well be different kinds of agreement. There may be agreement on distinct modes of mental functioning deployed, be it tension regulation, anxiety tolerance, self-reflectiveness, or object representations. However, we know that different analysts may focus upon or place greater or lesser emphasis on different aspects of the patient's productions. The history of efforts to determine analysts' agreement even among those sharing a common point of view, is replete with hurdles. Because it becomes even more difficult when analysts don't share the same point of view, another way of looking at the issue of congruence is from the vantage-point of pattern recognition. Thus, there may well be an overall agreement that patterns exist and that there is a shift in the trajectory of change, albeit the emphasis placed on the content that is observed varies, and even the nature, or significance, of the content varies, among the observers. It is only the first type of pattern recognition that we expect to pursue in this endeavor. Pass 4: External Validation The typed transcripts of sessions 232 and 226, as well as the transcripts from sessions 245 and 257 representing the second cycle, were subjected to an analysis of Computerized Referential Activity (CRA; Mergenthaler & Bucci, 1999). There is a special aspect in this approach to the analysis of text that resonates well with our earlier formulations, which have led us to describe a theory of change in the examination of clinical process. In the CRA analysis, each session is laid out in terms of successive word blocks over the entire session. This offers a space in which to describe a theory of change taking place over time, this time word block by word block. We are now in a position to trace the patterning of changes in referential activity, in emotion tone, in abstraction, and then in the extent to which these shifts are linked to analysts' interventions. It offers an arena for a focused analysis which may well allow for inferences not only about clinical description or clinical interpretations but perhaps also about regulatory principles. In Figure 3a we portray the CRA results for session 232, our 'A' session. It is a graphic representation of three units of observation, which comprise the referential process. Reading from top to bottom, we can see: 1) the language constituents (referential activity, emotion tone, and abstraction, expressed in standard score units as deviations from the mean); 2) patient or analyst speech (expressed as percent of total speech); and 3) number of work blocks (where each word block unit is 150 words).

A reading of the graphs for session 232 reveals an almost perfect referential process. It has a configuration of two waves - two cycles - separated by the analyst's intervention. The first cycle shows the sequence of referential activity, emotion tone, and abstraction. That narrative is then followed by the analyst's intervention, appropriately timed. The second cycle within this session, following the intervention, recapitulates the events of the first cycle, except with a stronger upsurge of emotional tone. The corresponding graphs for session 226, the 'Z' session, are shown in Figure 3b. The sequential arrangement of referential activity, emotion tone, and abstraction was quite different in this session. The analyst speaks a lot initially, then there is a long narrative, relatively barren in emotion tone, and then a good many interactions (analyst speech - patient speech - analyst speech, etc.), without the development of a reflective narrative or resolution. The coherent, integrated referential structure discovered in session 232 was not present in this session.

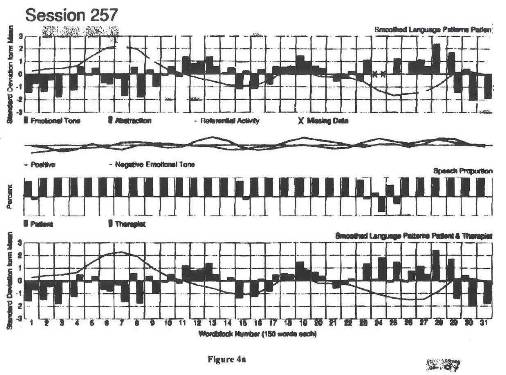

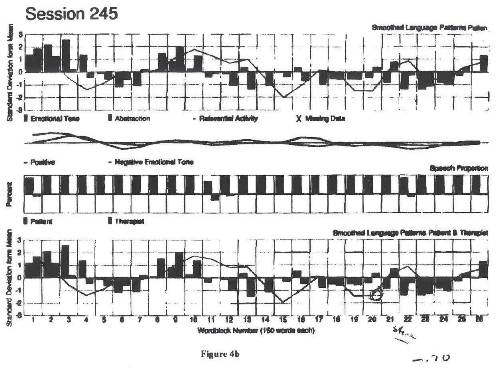

A further scrutiny of the graphs also reveals how different aspects of spoken language are integrated. In session 232, as one reads across word block units, one can see that emotional tone and abstraction tend to match each other, but they seem to be mismatched in session 226. The entry of the analyst occurs at the right moment in session 232, whereas the interventions are erratic in session 226. Could these be a sign of countertransference or mutual enactment? Finally, it is of interest to note that the number of word block units in session 226 was higher dm that of 232, but we know from our examination of markers of change in mental functioning that 226 had many fewer markers; that is, there were fewer shifts in how the patient's mental functioning was employed in session 226. It would suggest that in this 'Z' session, verbal output was more redundant. Here is an instance where the clinical understanding of the meaning of the utterances are necessary; we cannot just rely upon word output data. The referential process is most valuable to tell us where something important may be taking place. But to tell us what has taken place, we have to turn to other, more clinically-based sources of observation. In Figures 4a and 4b, we show the results of the replication of the referential process in another transformation cycle. In Figure 4a we show the graphs portraying the referential process for session 25 7, the 'A' session, and in Figure 4b we present the relevant data for session 245, a 'Z' session. Although there are interesting deviations, the patterns of 245 and 257 generally echo what we have just described for sessions 232 and 226.